Feature list

By @lucasdicioccio, 2684 words, 7 code snippets, 43 links, 3images.

Kitchen-Sink consists of two related components:

- i. a set of libraries (at the time of writing, everything is packed in a single library: it’s a kitchen sink afterall)

- ii. a default executable which uses defaults from the library

The library allows you to write a program to author websites from content thrown into a folder. The name Kitchen-Sink comes from the fact that Kitchen Sink is meant to work with a single folder having no particular organization besides filenames.

The executable imports the library to demonstrates and implements a blog-generator generating HTML having a default layout (for this very website for instance). Thus, as a Kitchen-Sink user you could either run the executable directly (if you want a website that looks like this one for instance) or write your own executable from the library.

When we refer to the Kitchen Sink engine or the blog engine, we thus refer to features available from the libary. As of this writing, however, I have yet to finish modularizing all these features. However, the following sections provide a listing of features with a good overall structure of what could go in which libraries.

command-line single-run mode

The default executable can run as a one-off generator command. The intended use-case if for generating websites as part of automated pipelines. There is nothing really exciting about the command-line single-run mode.

Example usage with the default executable:

kitchen-sink produce --srcDir website-src --outDir website-www

Loading (LoadArticle "website-src/features.cmark")

Loading (EvalSection "website-src/features.cmark" BuildInfo Json)

Loading (EvalSection "website-src/features.cmark" Preamble Json)

Loading (EvalSection "website-src/features.cmark" Topic Json)

Loading (EvalSection "website-src/features.cmark" Social Json)

Loading (EvalSection "website-src/features.cmark" MainCss Css)

Loading (EvalSection "website-src/features.cmark" Summary Cmark)

Loading (EvalSection "website-src/features.cmark" MainContent Cmark)

Loading (EvalSection "website-src/features.cmark" MainContent Cmark)

[...]

Assembling "website-www/features.html"

Assembling "website-www/topics/modding.html"

Assembling "website-www/topics/philosophy.html"

Assembling "website-www/topics/sections.html"

[...]

Generating "website-www/json/paths.json"

Generating "website-www/json/filecounts.json"

Generating "website-www/json/topicsgraph.json"

Generating "website-www/json/features.cmark.json"

Generating "website-www/json/philosophy.cmark.json"

[...]

These logs indicate that files where sourced in the website-src directory,

then computation occured, and finally files where output in the website-www

directory. You can navigate with a browser in this directory. However when

authoring articles it is pretty annoying to do manual refreshes. Instead,

Kitchen-Sink incorporates a server able to directly serve the same content as

it generates.

server-mode

One key reason for having written Kitchen-Sink is to explore things that makes my life easy. Among these: live

live-serving

Rather than generating all the website once, Kitchen-Sink can run an HTTP server that will directly return the results of the output targets on the fly. That is, each time a web-browser navigates, the latest value for a given route is shown to the browser. This is not especially useful but can come handy.

Example usage with the default executable:

$ kitchen-sink serve --srcDir website-src --outDir website-www --servMode SERVE --httpPort 7654

[...]

SiteReloaded (Init ())

SiteReloaded RunStart

TargetRequested "/features.html"

TargetBuilt "/features.html" 10079

GET /features.html

Params: [("server-id","ca231c17-35c9-4060-b4f4-c0dd574dd325")]

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Status: 200 OK 0.029790833s

TargetRequested "/js/search-box.js"

TargetBuilt "/js/search-box.js" 260790

GET /js/search-box.js

Accept: */*

Status: 200 OK 0.000694164s

Kitchen-Sink also supports HTTPS via TLS .pem key and certificate files.

$ kitchen-sink serve --srcDir website-src --outDir website-www --servMode SERVE --httpsPort 443 --tlsCertFile <mycert.pem> --tlsKeyFile <key.pem>

Note that if you run both HTTP and HTTPS the listening ports should differ. Plain-text (a.k.a., insecure connections) are disabled on the TLS server.

If you specify neither HTTP nor HTTPS the binary will load and exit immediately.

auto-reload

The executable server has a special API route with a mechanism to wait for changes of source files on the file-system. We also bundle a small JavaScript that subscribes to changes and reload the page on a change. This JavaScript gets injected in the layout only in dev-server mode. This setup allows to auto-reload on change.

To use the dev-server mode, use --servMode DEV. That is, the full-command to run with the default executable is:

kitchen-sink serve --srcDir website-src --outDir website-www --servMode DEV --port 7654

one-time commands

In addition to the above auto-reload script. The default executable’s layout insert some buttons to get one-click.

- the

producebutton will regenerate the whole HTML output - the

publishbutton will call thepublishScriptcommand in the kitchen-sink.json file . As a data-point, I use this publish-script for this documentation site.

API-proxy mode

KitchenSink, when acting as a server, will proxy calls on the /api route to a

web backend of your choice (configured in

kitchen-sink.json). This setup allows you to run

local development of single-page-apps against an API-server running aside. A

goal of this feature is to allow devs to build web-app without CORS or

HTTP-routing complications (concerns that should matter in production,

however). The only requirement (as of now) is that the proxified API uses the

/api route prefix.

When acting as a “multi-site” server, KitchenSink will furthermore allow you to

tune the default (30seconds) proxying timeout with the

--proxy-timeout-microsecs <delay-in-microseconds> command line argument. The

default timeout is 30 seconds.

it’s just a webserver library

I’ve not really explored this avenue, but it should be possible to incorporate the webserver logic in most Haskell web-applications (e.g., your web-application could run an API and Kitchen-Sink could run some documentation pages aside).

server metrics

Why not? to build the webserver-library I’ve used some set of curated and

bundled libraries named ProdAPI.

Which means the server inherits a number of features; among which a number of

Prometheus counters. An example set of metrics is

available on this

extract. Thus, rather

than bragging how much Kitchen-Sink is fast, you get to see for yourself

directly (e.g., with the blog_fullbuild_time counters in the Prometheus

summary). Other usages would be to track how fast you add content to articles

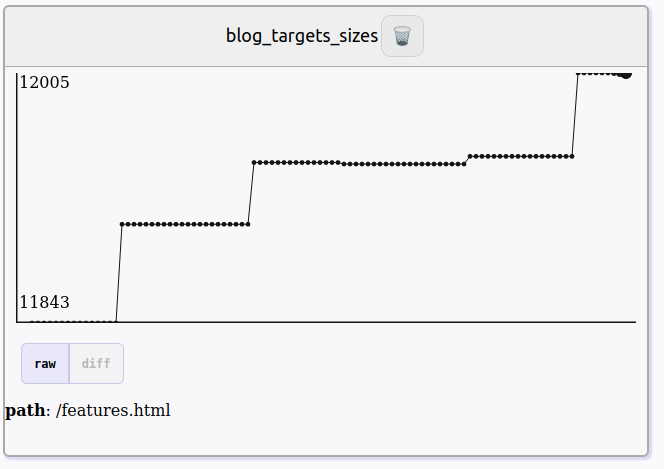

by collecting and storing the counters. For instance, the following picture is a screenshot of a Prometheus timeseries showing the size of the article

while editing this paragraph (screenshot is made using a Firefox extension I

built)

article authoring

Writing articles is the most important thing of a static-site generator. The Kitchen-Sink Philosophy here is to throw everything in one file. The key, and probably somewhat unique aspect of Kitchen-Sink is to propose writing articles, tune their CSS, provide topics, add generators and so on directly in the same source file.

the section-based format

The so-called section-based format has a dedicated article to document specific mechanism. In this article we merely show-off the source for this article to get an impression of what writing meaty content entails.

tunable CSS per page

Among sections worth a “feature” label, a special section drives the

inlined-CSS of individual articles. In short, each article can have its own CSS

file. I found that especially useful when I need to add some rules only for a

given article (e.g., alternating figure alignments) or when I want to host a

single-page JavaScript-app on an article only. Thus, you should use @import

directives for CSS modularization and re-use across pages. You do not lose

much in expressivity, a bit in performance, but you gain a lot in flexibility.

CommonMark as main input articles

Writing articles is mostly done in CommonMark. That is, the meaty content and some advanced analyses are based on CommonMark.

Besides the basics for headings, links, raw-HTML, emphasis, boldness, and code.

A number of extensions and additional extensions are enabled.

emojis 👀

Adding emojis is a way to incorporate some emotions in written-web content.

The list of :emoji-codes: is available ➡️ here ⬅️ 🔥.

delimited blocks divs with attributes

Which allow to add some CSS classes, and HTML identifiers

For instance:

::: {.todo #smalldiv}

add something

:::

generates the following code

<div id="smalldiv" class="todo">

<p>add something</p>

</div>which can then be styled in CSS.

syntax highlighting with skylighting

Code-blocks are analyzed by skylighting, which tokenize code and wraps resulting code with HTML tags having some well-defined classes for styling in CSS.

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

return 0;

}Overall I found that skylighting does the job and since the library requires no extra JavaScript on the resulting website or external-dependencies at code-generation time: it’s good.

HashTags

This extension is custom-made (until we upstream it). KitchenSinks discovers #hash-tags in artcicles. Such a feature enables you to turn your blog into some #note-taking apps. HashTags acts like Topics in the sense that they allow you to list all items on a special, per-HashTag page.

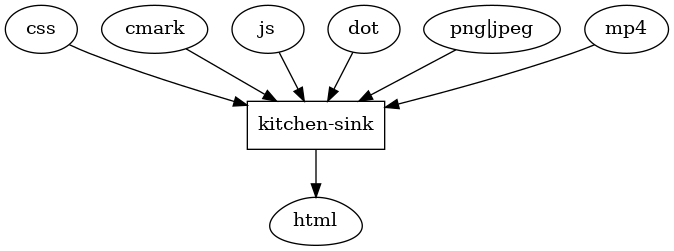

copies other images, css, medias

An article often comes with extra medias. Images (with jpeg, png

extensions), JavaScript (.js) and CSS (.css) files are copied to

their own target at known locations. The same thing occurs for a variety of

filetypes (.mp3, .mp4 and so on).

That is, KitchenSink wants everything in a directory but applies rule so that

you get something a bit cleaner in return, isn’t it awesome?

You can see for yourself, compare the listing of this website source directory with the listing of the website output directory (courtesy of tree -J).

generate images from .dot

There is a special room in my heart for GraphViz ❤️. I use it a lot to render diagrams and illustrate simple ideas. Thus I found natural to add some special support for files with the .dot extensions.

Coupled with auto-reload, GraphViz-made diagrams work well enough to edit technical articles without ever leaving my editor as illustrated in the following video:

content-generation

The core-business of a static-site generator is to generate HTML output from various input. Thus, we could pedentically say that all content is “generated”. Here we discuss cases where Kitchen-Sink goes the extra-mile to provide extra features.

embedded data

Kitchen-Sink generate a host of data while assembling targets from input files.

Intermediary-representations. In particular, there is a json file generated

with each HTML article and is linked in the HTML meta tag with name

ks:article_json (generally at the special location /json/<my-article>.cmark.json). So that individual scripts can then locate these

information. As we get more mileage, we’ll likely add more of such paths and

formalize a bit their expected content. However, keep in mind that

Kitchen-Sink generates more than just the static aspects of the HTML: it

provides a bunch of extra information which can be useful for creative and advanced analyses.

[experimental] textual output for AI agents

In this day and age of AI agents, providing a textual output can help reduce

tokenization and processing costs. Kitchen-Sink generates a text file for

each HTML article. This text-file is linked in the HTML meta tage with name

ks:article_text (generally at the special location

/text/<my-article>.cmark.text). Since some amount of text can be generated at

load time, we cannot just serve the source code. This renderer is experimental.

command-based generators

In this article I’ve already pointed to a number of links (e.g., the source of this article, some directory listings). In short, you can add one-off data collections that produce their own targets.

A typical usage is to turn some information about the system generating the

blog (e.g. uname -a). However you could get creative such as

- fetch the latest news-article

- run some database query to be displayed in javascript later

Less typical usage is for “personal” features like taking a selfie on demand:

yes, this picture happens to be my face when I generate my personal

blog as I’ve added this section in the

“about-me” page – hat tip to fswebcam.

=generator:cmd.json

{"cmd":"fswebcam"

,"args":["-r", "320x240", "--jpeg", "85", "-D", "1", "/dev/stdout"]

,"target":"latest-selfie.jpg"

}

Another fun usage is to roast your articles, provided a script I made called ollama.sh, the following uses an LLM to roast an article (example at a generated-file path). Here I’ve used the Dhall section (see below) so that the source-path is accessible to the generator command.

=generator:cmd.dhall

let cmdcontent =

{ cmd = "ollama.sh"

, args =

[ "task-file", "you are given a source file of a blog post, the content resides below a =base:main-content.cmark marker. comment on the article by giving honest feedback in a sarcastic manner"

, kitchensink.file

]

, target = "roast-me"

}

in

{ contents = cmdcontent

, format = "json"

}

microscriptable in Dhall

I have written a full article on my personal blog a while ago to motivate the whole usage of Dhall. Keep in mind that I’m still happy about the choice. Dhall “powers” my photo galleries and my stream of notes on my personal blog.

article organization

An article needs some decorum to help readers of your site as well as other applications relaying your articles. For instance, who is the author? what topics are covered? can you summarize it for me? Kitchen-Sink has a number of features to answer such questions. Most if not all of these features are controlled by specific sections in the section-based-format. Here we merely give an overview of what is feasible.

categories and series using topics

Article can be labelled with a set of topics. Kitchen-Sink then collects all

articles for a given topic under special categories and under the /topics

route. This is not especially innovative but I believe it’s a must have even if

I suppose most readers do not really use these topics listing a lot, they are

used to connect articles in the site map graph.

Furthermore topics double as series that is, a “previous/next” link show up on the article header. To follow the previous-next article within a topic.

article summaries

Article have summaries. The use case for summaries is to entice readers into committing more time to read an article in full.

Technically, summaries are inserted in article listings. The main listing is

the home-page of a blog. Categories listings also

repeat the listings. The summary also is used in some <meta> headers, in

particular to provide neat summaries when people share your articles (cf. open-graph).

social links

In this age of pervasive Internet, you may have accounts in a number of online social-networks. Kitchen-Sink supports some of these: list your handles and enable features (as of today: it’s only a link to your canonical profile, in the future we could imagine more interactions).

open-graph and twitter-card metas

You’ve probably already seen how some chat-applications (e.g., Discord, Slack)

and social-services (e.g., LinkedIn, Twitter) provide a preview of webpages

that are linked. These previews can embed images. You need to follow some

specifications to control these, and that is what Kitchen-Sink does. Indeed

Kitchen-Sink generates <meta> HTML headers for OpenGraph

and Twitter

cards.

consolidated glossary

KitchenSink allows you to add glossary items to individual articles as well as a consolidated glossary where multiple definitions may coexist.

content-analysis

Whether you write individual articles or a long series of multiple articles, it is useful to have some way to summarize what you have written. For instance, you want to know whether an article is connected to other articles, you want to understand if sections are well-balanced or not.

All of these reasons were decisive factors when deciding to write and while designing Kitchen-Sink. I’ve merely scratched the surface of the analyses I want to make on my own writing and I hope you’ll find some of these helpful too.

Atom feeds

KitchenSink generates a Atom feed for the whole site at the /atom.xml path as well as one Atom feed for each of the topics listing. In short: every topic is its own Atom feed. For now only summaries in raw text format are provided.

sitemap

KitchenSink generates a sitemap.txt linking to all articles.

Remember to “ping” Google afterwards by visiting

https://www.google.com/ping?sitemap=<your-deploy-url>/sitemap.txt (I’m not an SEO expert so I cannot really vouch for other crawlers).

site listing and search-box

Static sites lack a good user-driven search as there are no servers to answer search queries. Topics listing alleviate some of these need. Topics merely are pre-computed indexes (and Atom feeds). Thus, KitchenSink also want to pre-compute search indexes. At the moment, the search-box is primitive and only allows to search into filenames (and I use it all the time when authoring articles to find links to images and generated outputs). However we could definitely go a step further by also searching, or displaying summaries in the search box. As people say: watch this space!

wordcounts and article staircases

One key aspect of writing content for the web is to control the length of an article. While writing for a printed format (my experience is with academic publishing) the number of pages and the number of column-per-page for articles is a good indication of the size of the content. Infinitely-long pages on the web blur this signal. Thus, to rebuild some understanding of how-long an article is, we need to run word counts.

As a result, Kitchen-Sink compute a word count for each article (in addition to images, links counts). Even further, Kitchen-Sink computes a word-count per title-section. Which allows us to display what I call article staircases with visualization libraries (here we use Apache ECharts):

The above histogram shows, for each section in the article, the number of words and the cumulated number of words in the article. This histogram allows me, when writing an article, to spot which sections are abnormally-long or abnormally short. I interpret this graph to find opportunities to split or merge sections together, hopefully improving my writing for users.

Kitchen-Sink also computes whole-site summaries although I have no great use-case yet for these.

sitemap graph

Kitchen-Sink processes all of the above information (topics, links between pages, image lists, etc.) to populate a JSON representation of a graph summarizing the structure of the whole site. This special target is built with the website and you can be creative with it. So far, Kitchen-Sink provides a PureScript compiled to JavaScript minimal app to turn the graph into an interactive-picture using Apache Echarts.

A special config in kitchen-sink.json allows to give extra importance to a subset of externally linked sites. For instance a connection between this page and a random WikiPedia article exists because we defined an entry for WikiPedia. Think of this feature like a revisit of the good-old webrings.